Variola: A Scourge Silenced – The Unprecedented Eradication of Smallpox

In the annals of human history, few victories against disease shine as brightly as the eradication of Variola, commonly known as smallpox. This infectious disease, once a global terror, claimed millions of lives and left countless survivors disfigured. Caused by the highly contagious Variola virus, a member of the Orthopoxvirus genus, smallpox systematically ravaged populations for millennia. Yet, in a monumental triumph of global public health, Variola became the first – and to date, only – human disease to be completely wiped off the face of the Earth. Its eradication stands as a testament to scientific dedication, international cooperation, and the power of vaccination.

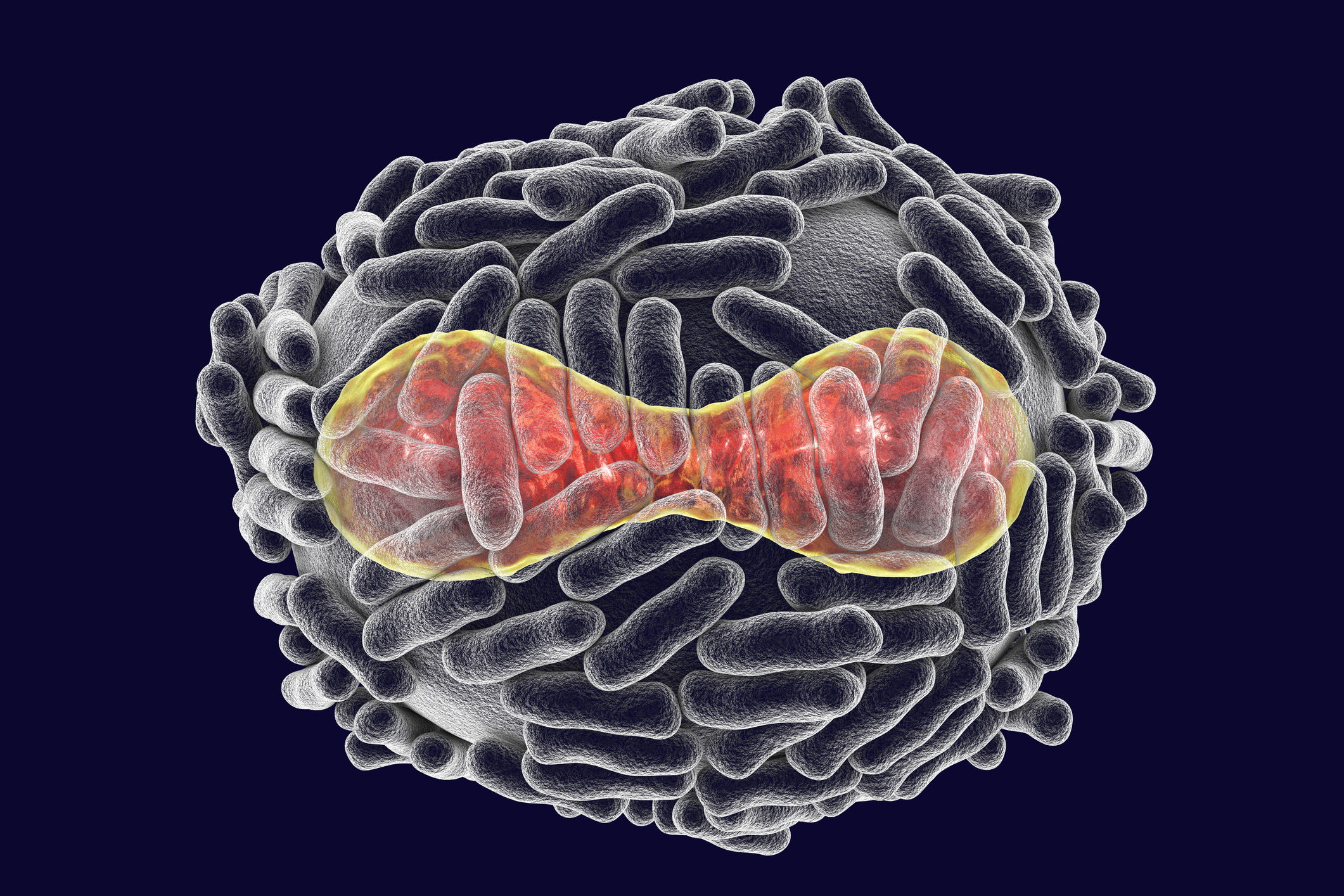

The Variola Virus: Understanding the Pathogen

The Variola virus is a complex double-stranded DNA virus with a relatively large genome. It specifically targeted humans, making it a particularly devastating pathogen. Unlike some other infectious agents that can jump between species, the Variola virus had no known animal reservoir, a critical factor that ultimately contributed to its eradicability. Transmission occurred primarily through airborne droplets expelled from the mouth and nose of infected individuals, making close contact a high-risk scenario. The virus could also spread via contaminated objects, though this was less common.

Once contracted, the incubation period for Variola typically ranged from 10 to 14 days, during which time the infected person showed no symptoms but was silently carrying the potent pathogen. This period of asymptomatic incubation, while relatively short, allowed the virus to spread insidiously within communities before the tell-tale signs became apparent. Understanding the epidemiology and unique characteristics of the Variola virus was crucial for designing the targeted intervention strategies that would eventually lead to its demise.

The Dreaded Progression: Symptoms and Clinical Forms of Smallpox

The onset of smallpox was abrupt and severe, marked by a constellation of debilitating symptoms. The Latin term "Variola" itself, derived from "varus" meaning knot or spot, vividly describes the disease's most feared characteristic. Initial symptoms, known as the prodromal phase, were non-specific but intensely distressing:

- Sudden onset of high fever: Often reaching dangerous levels.

- Chills and rigors: Indicating a systemic inflammatory response.

- Severe back pain (Kreuzschmerzen): A particularly characteristic and agonizing symptom.

- Headaches and profound malaise: A general feeling of extreme unwellness and lethargy.

- Vomiting and anorexia: Leading to dehydration and nutritional deficits.

- Oral lesions: Ulcers in the mouth and throat often appeared early, making eating and drinking painful and contributing to early infectivity.

Following this initial phase, a distinctive skin rash would emerge, marking the eruptive stage. This rash, which defined the disease, progressed through several identifiable stages over several days:

- Macules: Small, red spots appearing on the face, hands, and forearms, then spreading to the trunk. Sometimes an initial, transient rash (initial exanthem) could appear on the thighs or abdomen before the main Variola exanthem.

- Papules: The macules quickly developed into raised bumps.

- Vesicles: Within a couple of days, these papules would become fluid-filled blisters.

- Pustules: By around the 6th day of eruption, the vesicles would turn into pus-filled lesions, characteristically deep-seated, round, and firm to the touch, with a distinctive central depression or "umbilication" (Pockennabel) and often a dark, swollen rim. This stage was typically accompanied by a resurgence of fever, signalling the body's continued struggle against the infection.

- Crusts (Scabs): Over two weeks, the pustules would dry out, forming thick scabs that eventually fell off. This "Stadium exsiccationis" marked the end of the active eruption, but the scabs remained highly infectious.

The scabs, especially prominent on the face, would often leave behind deep, pitted scars, a permanent and disfiguring legacy of survival. While recovery was possible, death remained a significant risk even after the pustular stage, and the suffering was immense. For more in-depth information on the various presentations and progression of the disease, you can refer to Variola Virus: Smallpox Symptoms, Progression, and Types.

Clinical Variants and Their Severity

Not all cases of Variola were identical in their presentation or outcome. Doctors recognized several clinical variants, each with differing levels of severity:

- Variola Vera: This was the most common and severe form, characterized by the typical progression of a widespread, dense rash. It had a high mortality rate, particularly among unvaccinated individuals.

- Variola Haemorrhagica: Known chillingly as "black pox," this was the most lethal form. Instead of typical pustules, patients developed extensive hemorrhages into the skin, mucous membranes, and internal organs. The skin would appear dark, almost black, due to these vast internal bleedings. It progressed rapidly and was almost uniformly fatal within 3-5 days of onset, leaving little chance for intervention.

- Variola Mitigata and Variolois: These were milder forms of the disease, often observed in individuals who had been previously vaccinated or had some partial immunity. In these cases, the rash might be sparse, the lesions might not progress fully to the pustular stage, or they might dry out without extensive pus formation. They could even manifest as small nodules that, upon drying, left a warty elevation (Variolois verrucosa). While less severe, these forms were still infectious and could be misleading diagnostically.

Early diagnosis was critical, and identifying the characteristic sudden onset with chills and severe back pain was a key indicator. Microscopically, the presence of Guarneri bodies within infected cells was a diagnostic hallmark. For a deeper dive into how these distinctions played a role in understanding and combating the disease, see Understanding Variola: From Blisters to Global Eradication.

The Global Eradication Effort: A Public Health Masterpiece

The story of Variola eradication is one of humanity's greatest public health achievements. Recognizing the immense suffering and mortality caused by the disease, the World Health Organization (WHO) launched an intensified global eradication campaign in 1967. This audacious goal was met with skepticism by some, but propelled by unprecedented collaboration and a highly effective vaccine derived from vaccinia virus, the campaign pressed on.

Key strategies of the eradication program included:

- Mass Vaccination: Wide-scale immunization campaigns were undertaken, aiming to reach every corner of the globe. The smallpox vaccine was incredibly effective, providing long-lasting immunity.

- Surveillance and Containment: Rather than solely relying on mass vaccination, the strategy evolved to include "ring vaccination." Once a case was identified, health workers would quickly identify and vaccinate all contacts of the infected person and those in their immediate vicinity, forming a "ring" of immunity around the outbreak to contain its spread.

- Targeted Search and Isolation: Active searches for cases, particularly in remote areas, were crucial. Patients were isolated to prevent further transmission.

- Global Coordination: The WHO provided leadership, resources, and technical support, coordinating efforts across diverse nations and cultures.

The dedication of thousands of health workers, often operating in challenging conditions, was paramount. They trekked through jungles, deserts, and war zones, administering vaccines and tracking down every possible case. Their efforts paid off. The last naturally occurring case of smallpox was diagnosed in October 1977 in Somalia, a pivotal moment in medical history. Three years later, in 1980, the WHO officially certified the global eradication of smallpox, declaring the world free from this ancient plague.

Legacy and Lessons Learned from Variola's Eradication

The eradication of Variola is more than just a historical footnote; it offers invaluable lessons for contemporary global health challenges. It demonstrated that a disease can indeed be eradicated with a combination of a potent vaccine, sustained political will, robust surveillance, and unwavering public health commitment. The economic benefits have been enormous, saving billions of dollars annually that would otherwise have been spent on treatment, prevention, and managing the long-term consequences of the disease.

The success story of smallpox has inspired and informed subsequent eradication and elimination efforts for other diseases, such as polio and measles. It underscores the critical importance of strong public health infrastructure, accessible vaccination programs, and international solidarity in confronting shared threats. While the Variola virus no longer circulates naturally, samples are still held in secure laboratories, primarily in the United States and Russia, for research purposes. This has sparked ongoing debate regarding the ethical implications of retaining such a dangerous pathogen, even under strict containment, highlighting the need for continued vigilance and scientific responsibility.

The triumph over Variola serves as an enduring symbol of human ingenuity and collective action. It reminds us that even the most formidable health challenges can be overcome when science, compassion, and global cooperation converge.